Inflation Reduction Act Favors Biologics Over Small Molecules: In The Long Term, This Could Partly Undermine Bill’s Effort To Contain Costs

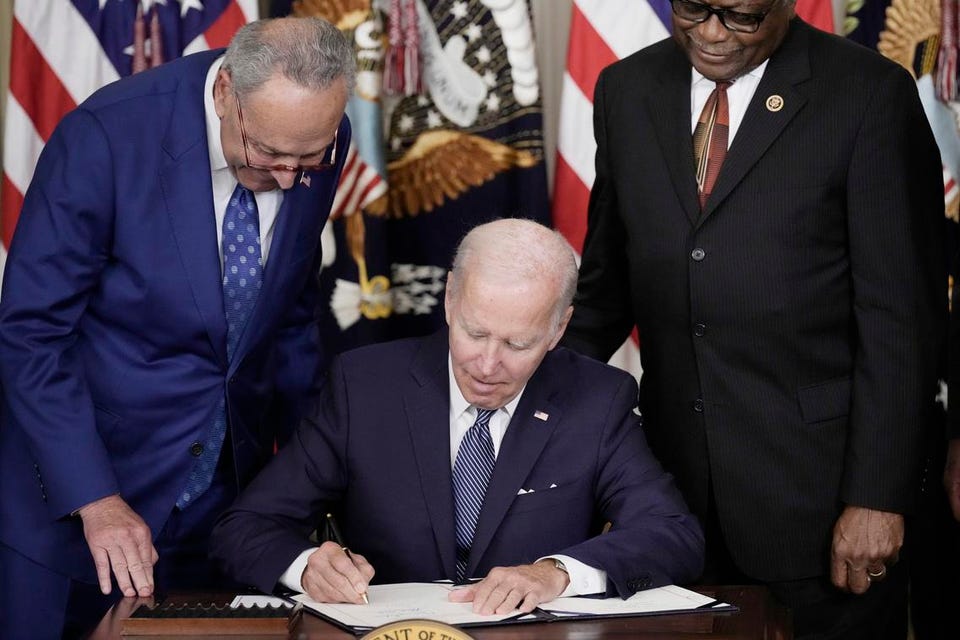

WASHINGTON, DC – AUGUST 16: U.S. President Joe Biden (C) signs The Inflation Reduction Act with … [+] Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer (D-NY) (L) and House Majority Whip James Clyburn (D-SC) in the State Dining Room of the White House August 16, 2022 in Washington, DC. The $737 billion bill focuses on climate change, lower healthcare costs and creating clean energy jobs by enacting a 15% corporate minimum tax, a 1-percent fee on stock buybacks and enhancing IRS enforcement. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Getty Images

The Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) drug pricing provisions include as one of three main pillars, drug price negotiations between Medicare and drug makers for a limited subset of pharmaceuticals. Currently, the IRA has two different timelines for large and small molecule therapeutics: Large molecules – biologics – can be selected for negotiation 11 years following approval, while small molecule drugs are eligible 7 years after approval. For those biologics that are selected for price negotiation, their negotiated “fair prices” will be implemented 13 years after approval, while for small molecule drugs their prices will be enacted 9 years after approval.

Because the law gives small molecule drugs a shorter, 9-year post-approval window before their “fair prices” are implemented, executives in the pharmaceutical industry have argued that the IRA will “harm innovation,” in particular, with respect to small molecules.

Several drug companies have publicly stated that they’re terminating a number of small molecule drugs from their pipeline. In addition, the trade group PhRMA said that in a survey it conducted 63% of member companies expect to shift at least some of their research and development investment away from small molecule medicines.

The drug industry can be prone to hyperbole. So, when a senior executive declared recently that “in 10 years, we’ll have far fewer small molecules being developed than we do today,”* this seems more rhetorical than reality-based. It is certainly not consistent with a CBO report, which concluded that the legislation would have a “very modest impact on the number of new drugs coming to market in the U.S. over the next 30 years.” In sum, the IRA is not going to devastate the industry.

Moreover, when drug makers say they are now prioritizing biologics, surely that’s not just related to the IRA. There’s much more to it than that. In recent years, there’s been a shift towards biologics, which include gene therapies, as the industry has increasingly focused on disease areas in which biologics play an important role, including multiple cancers, autoimmune diseases, and numerous genetic disorders.

Nevertheless, the skewing of incentives away from small molecule development may have unintended consequences over time. The dropping of early-stage small molecule programs is a potential concern, especially as this may lead to a disproportionate emphasis on biologics development. In turn, this could ultimately undermine in part one of the purposes of the bill, which is cost containment.

Small molecules comprise 90% of all pharmaceuticals, and even in the past decade – a period during which biologics have steadily gained share of new approvals – a majority of newly approved drugs. Small molecule drugs have relatively simple, stable chemical structures that are comparatively easy to formulate and administer. Also, once a branded drug patent expires, a bioequivalent small molecule is easy and cheap to reproduce as a generic; in fact, much easier and substantially less costly to replicate than biosimilars. More than 92% of scripts in the U.S. are for small molecule generics. On the other hand, biologics tend to have a higher price tag, and when they are confronted with competition in the form of biosimilars, originator biologics don’t face nearly the same price or market share erosion as is the case with small molecules.

It’s unclear why the IRA was crafted in such a way as to incorporate a four year difference in eligibility for price negotiation between large and small molecules. A plausible explanation is that there is currently a disparity in exclusivity in the U.S. of 12 years for biologics versus 7 years for small molecules. Additionally, legislators may intentionally be promoting future biologics (including gene therapies) development, as they view it as more cutting-edge and able to better address certain unmet healthcare needs.

But, even a modest change in allocation of investment funds from small molecules to biologics and cell and gene therapy programs – amplifying what’s already been occurring – will yield relatively more higher-priced products at launch. Of note, the IRA doesn’t include any restraints on the launch prices of any type of biopharmaceutical or therapy. In addition, biologics are typically not available for self-administration at home and require infusion, usually in a much more expensive setting like a hospital or physician’s office.

Peter Kolchinsky – managing partner at RA Capital – has long maintained that the 9 years for small molecules is too short a period in which to expect a reasonable return on investment. I have my doubts about whether the tail end of products’ revenue cycles will be as crushed by the IRA as Kolchinsky and others predict. In the current system – without the IRA’s price negotiations in effect – pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which operate Medicare Part D plans, already negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers. While they don’t do this collectively as a monopsonist (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)) will for a limited subset of drugs under the IRA, they can and do exert substantial downward pressure on net prices, particularly with respect to the types of drugs targeted by Medicare for negotiation in the IRA. It is highly probable that by the time these drugs’ exclusivity periods are about to expire they’re in direct competition with others in the same therapeutic class. Correspondingly, the more competitive a therapeutic class the steeper the rebates and the lower the net prices.

Nonetheless, it would be folly to ignore what investors like Kolchinsky are saying. They’re forward-thinking, meaning they anticipate future returns based on expected factors that impact the market. As such, they expect to see relatively more money to flow to more costly biologics. Accordingly, that may spell trouble for pharmaceutical and other healthcare costs down the road.

Kolchinsky proposed a budget-neutral fix to the bill that would even the playing field between small and large molecules, specifically by making implementation of fair prices for both types of molecules, 13 years. At the same time, Kolchinsky suggested that the minimum discount to establishing fair prices for small molecules be increased to retain budget neutrality.

This amendment to the legislation hasn’t happened. However, it’s not out of the question that some kind of change could occur at some point. After all, as CMS prepares to operationalize and execute the IRA’s drug price negotiation provision, the agency appears more than willing to listen to and perhaps accommodate the public’s suggestions.