Uber’s New Math: Increase Prices And Squeeze Driver Pay

Uber has been a poster child of US zero interest rate policies (ZIRP) over the past decade, stimulating unprecedented levels of private and public capital investment in companies pursuing of global domination — profits be damned. Between its venture capital funding rounds and IPO, Uber raised $32 billion before and during CEO Dara Khosrowshahi’s reign, fueling the dubious distinction of raising and losing more money than any startup in history.

Until this year, the company was making a perfectly logical choice to deploy its bountiful capital to push for growth over profits, mirroring investor priorities in the cheap money era. In fact, Dara (as he is often, familiarly called) lost more money during his first four years as CEO than founder/CEO Travis Kalanick did during the company’s first six years.

But times (and interest rates) have changed, prompting Dara to now espouse the new math he described on a recent podcast:

“It’s about math and math always wins. And the math for a company getting to cash flow breakeven is you have to grow your revenues faster than you’re growing expenses.”

For Uber, having already shed a number of ancillary money-losing businesses, this translates into raising prices and squeezing driver pay — by far the two biggest drivers of the company’s financial performance. So let’s dig into some key facts and figures to see how Uber’s new math has been working, using third-party data to peer into the company’s US ridehail operations — the company’s biggest business unit.

Uber began raising US ridehail prices at a double-digit percentage clip in 2018 as the company prepared for its 2019 IPO, and has continued hiking prices ever since. According to data provided to the author by Second Measure, Uber’s average US ridehail fare per trip jumped by 30% from the beginning of 2018 to Q3 2019, and then, according to data from YipitData, by another 41% between Q3 2019 and Q3 2022 – for a total of 83% over the entire 45-month period. This is equivalent to an annual price increase of 17.5% per year, considerably exceeding the CPI gain of 4.5% per year over the same period.

While Uber’s price escalation succeeded in boosting its mobility revenue – ridesharing demand is inelastic, at least at historical price levels — it also depressed consumer demand growth. According to tracking data from YipitData, Uber’s US ridehail trips in Q3 2022 decreased 29% from pre-pandemic Q3 2019 levels, offset by the price hike of 41% over the same period. In essence, Uber has traded off decreased ridehail demand (as measured by number of trips) in exchange for increased revenue and profitability.

I’ve had to rely on estimates from independent sources for this analysis, because Uber has never disclosed data on its consumer prices, driver pay or trip demand trends for its US (or any other country’s) ridehail operations. More on this point later.

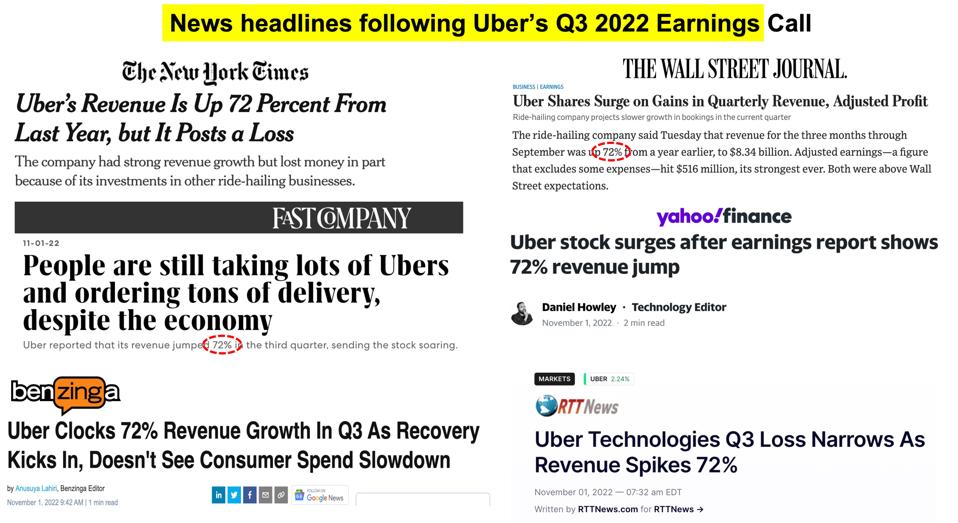

Zooming out now to examine Uber’s global financial results, on his Q3 2022 earnings call, Dara crowed that “Uber’s core business is stronger than ever,” exemplified by the company’s 72% Y-O-Y revenue growth rate. The business press widely highlighted this impressive figure in their headlines and story ledes.

Uber

Author curated news stories

But Uber’s reported revenue growth rate was significantly inflated by a material change in its Mobility and Delivery revenue accounting as well as by an acquisition in its Freight division, both of which were conveniently buried in an earnings report footnote but overlooked in Dara’s commentary and widespread press coverage. After properly adjusting for these anomalies, Uber’s actual Q3 2022 Y-O-Y core business (Mobility and Delivery) growth was only 26.5%, and much of that was driven by take rate increases – the spread between prices and driver pay — not underlying growth in consumer demand or productivity improvements.

These deep-in-the-weeds adjustments may seem like TMI, but they are important, because going forward, Uber will not be able to achieve anything near their impressive, but misleading Q3 2022 reported growth rates, for three reasons.

Most of Uber’s reported revenue growth was driven by one-off events, not sustainable improvements in business operations. Obscured accounting changes will eventually – actually, quickly – be recognized by savvy investors. For example, while Uber enjoyed a 12% pop in its stock price the day of its rosy Q3 pre-market earnings release, its stock has slid 17% over the ensuing two months Uber’s future revenue growth rates will be pegged to recovering post-pandemic demand, not the deeply depressed pandemic levels that have boosted recent Y-O-Y revenue gains. For example, adjusted for accounting changes, Uber’s Q3 2022 YTD Mobility and Delivery global revenues have only grown 17.5% and 6.5% respectively, compared to the 47.7% and 26.9% respective figures for Q1-Q3 2022 on a Y-O-Y basis. There are limits to Uber’s ability to continue to achieve revenue growth by raising prices, particularly entering a period of macroeconomic uncertainty. For historical context, Uber’s US mobility trips and bookings growth declined markedly in 2018-2019, when Uber first began aggressively raising ridehail prices.

After adjusting for accounting changes, Uber’s core business (Mobility + Delivery ) growth rates YTD 2022 vs. 2021 were:

Bookings: 24.7% Revenue: 37.7%

There are only three ways that Uber can enjoy significantly higher revenue growth than bookings growth in their core business:

Improve productivity (for example batched delivery orders or pooled ridehail operations), so that Uber (and perhaps drivers) can enjoy more revenue per trip Generate additional sources of revenue from activities outside core platform bookings – e.g. advertising on Uber’s platform Increase take rates by charging passengers higher fares that are disproportionately retained by Uber and/or by lowering driver/courier compensation per trip

For starters, let me state a frustrating caveat. Uber has never disclosed sufficient data to allow a fully substantiated assessment of its operational and financial performance. So what follows is my best-efforts hypotheses.

1. Improved productivity

Over the years, Dara has repeatedly made vague references to “improved operational efficiencies” and “algorithmic improvements” without clarifying what levers have enabled improved performance. I suspect that Uber’s actual productivity improvements have been minimal. In ridehailing, the most obvious productivity enhancer is pooled ridesharing. With its dominant market share, Uber is in an advantaged position to be a leading pooled ride market-maker. But in fact, Uber has never been able to build a pooled service that widely appeals to riders or drivers. So while Uber doesn’t break out its demand numbers, there is no reason to believe that pooled rides have been a major driver of higher revenue and take rates for Uber.

On the delivery side, the most obvious productivity enhancer is batched orders. But this tactic adds logistical complexity and degrades food quality and customer satisfaction. Therefore, I’m skeptical that order batching has materially improved Uber Eats’ economics of late. Uber can certainly dispute this hypothesis by sharing trend data on its gross merchandise value (GMV) per trip or its orders per driver per hour. I’d welcome being proven incorrect on my assumption

Another potential revenue enhancer is increasing ridehail use and/or delivery GMV and order frequency for customers enrolled in the Uber One loyalty program. But the impact of this program on Uber’s economics is unclear. Uber trails DoorDash in its loyalty program penetration, and neither company has disclosed the extent to which their loyalty programs generate net revenue and profit improvements after accounting for discounted fares and delivery fees.

2. Additional revenue drivers

Advertising is a potential game changer. For example, some reports suggest that Amazon’s global ecommerce business would be unprofitable were it not for the substantial additional revenue earned from merchant advertising (currently generating $40 billion revenue per year!) . Uber has already been accepting ads on its Eats platform for a couple of years, and has recently added ad banners to its ridehail app. But these ad programs have yet to achieve the scale to account for the recent sizable difference between Uber’s revenue and bookings growth rates. Perhaps ads will become a significant revenue generator down the road, but not yet.

3. Raise ridehail passenger fares and delivery fees and/or squeeze driver pay

These are the actions that undoubtedly are driving Uber’s recent financial performance improvements and the clearest manifestations of Dara’s “new math” to grow revenues (passenger fares) faster than expenses (driver pay). The sketchy data Uber does disclose confirms that the company has been increasing its take rates over the past few years. As already noted, passenger fares have been trending significantly higher for the past five years. While driver comp data is harder to come by, Uber’s recent shift to “upfront prices” has effectively decoupled consumer prices and driver pay from actual travel time and distance, giving the company cover to increase the spread between consumer prices and driver pay.

And in this regard, Uber enjoys a massive competitive advantage: more data on consumer and driver behavior on a global scale than any other mobility or delivery provider. Armed with such market insight, Uber is in an ideal position to practice what economists call first-order price discrimination — that is, charging each customer prices based on their known willingness to pay and setting each driver’s pay based on their known willingness to serve. The resulting upside potential of such price discrimination is enormous, and the opportunity (massive data + AI algorithms + upfront pricing policies) and need (growing investor pressure for near-term profitability) to exploit it is urgent.

Uber has historically denied (without evidence, of course) that they in any way set prices or pay based on individual passenger or driver characteristics. However, their recent tactics de facto promote a race-to-the-bottom in driver pay by operating a bidding process on their driving app where competing drivers have literally seconds to accept low pay offers (usually after Uber’s initial low pay offer to a specific driver was rejected). Anecdotal evidence also suggests that Uber may be using similar tactics to set and revise passenger fares, lowering only after a passenger rejects its initial higher price offer.

To be clear, there is nothing illegal about discriminatory pricing, as long as it’s not based on customer gender, race or ethnicity. And it’s perfectly understandable that Uber would consider such tactics, given the enormous pressure Dara is under to finally reach its Sisyphean quest for profitability. After all, despite potential reputational risks, it’s hard to ignore what may be Uber’s best profit driver and possibly only true source of competitive advantage. And it’s also understandable why Uber would be reluctant to talk about what would likely be viewed as deeply unpopular pricing and pay tactics.

Nonetheless, the current state of play raises some troubling questions. Travis Kalanick launched Uber over a decade ago with the promise that Uber would make “transportation as reliable as running water, everywhere, for everyone.” His successor, Dara Khosrowshahi modified the company’s mission to become “the operating system for your everyday life,” and “a technology company that connects the physical and digital worlds to help make movement happen at the tap of a button.”

But what we have gotten instead is company that has disappointed investors and built a marketplace where passengers and drivers don’t know what price or pay to expect from trip to trip, while merchants face stiff fees, the loss of customer relationships, and frequently spotty service for delivered goods (Uber Eats’ NPS consumer satisfaction score is 11 out of 100). And recently, riders and drivers appear to have been increasingly drawn into an algorithmic pricing game where Uber stacks the cards in the house’s favor.

These dynamics are carefully hidden behind Uber’s veil of secrecy about its actual operational and financial performance. Given its carefully curated and limited disclosures, investors and business analysts and the press know shockingly little about even the most basic measures of Uber’s performance, including:

How many US ridehail trips did Uber provide this quarter? What was the average price and driver pay per trip? What is the distribution of ridehail take rates? What is the average and distribution of actual passenger wait times … and similar questions for Uber’s delivery operations

Uber isn’t the only company that has been extremely stingy in reporting meaningful operational data. But its secretive nature is particularly distressing for two reasons:

Uber serves a pivotal role in providing mobility for tens of millions of consumers. Other entities in a similar role – public transportation systems and airlines for example – routinely report detailed data on their fare levels, employee pay, on-time performance and other metrics of operating performance that are in the public interest to know. Dara regularly punctuates his preternatural optimism — damn, he’s good at happy talk! — with undefined or unsupported business factoids in interviews and analyst briefings. For example, our “drivers are now earning $39 per hour!” or “passenger demand is back!.” And yet, whenever analysts cite independent data suggesting less robust Uber’s performance (e.g. YipitData, Gridwise), the company’s predictable response is “their analysis was based on incomplete and inaccurate data.”

If Uber is to be given credit for fulfilling their grand promise of becoming the transformative future of urban mobility, investors, consumers, and drivers deserve to know a lot more about the real costs of being taken for a ride.